I have been a fan of the number nine since, well before I hit double digits, I started to notice number patterns.

I liked how it could be made by placing three light green cuisenaire rods side by side into a 3×3 square, and how that square plus a 4×4 made a 5×5 – the quintessential example of what our brusque but caring, number-loving 6th class teacher, Miss Bryan, was later to reveal as Pythagoras’ theorem in a lesson surely so enchanting that she felt no need to threaten to have our “guts for garters” in her Yorkshire brogue.

I liked how its proximity to the number ten, inscribed in its Roman form IX – one less than X – shapes and simplifies its calculations. Add 10 and subtract 1. Or multiply a number by 10 (by sticking a zero on the end) and subtract the original number. This also leads to the very cool fact – useful for factorising – that for any multiple of 9, the sum of the digits is also a multiple of 9, and you can continue this process until you get a single digit 9. For example, for 3,285 the sum is 3+2+8+5 = 18, and then 1+8 = 9; conversely for 3,287, the sums are 20 then 2, so this is not a multiple of 9 (not coincidentally, a similar trick can be used to identify multiples of 3).

But now, today, I am even more a fan of the number 9. For today – 7 January 2022 – is the 9th anniversary of my MND diagnosis, an anniversary which for so many of those 3,287 days (Leap Years included) I did not expect to make.

I did not expect to make it on that terrible, scorching Monday morning, 9 years ago, when Densil and I were given the news that would bifurcate and dislocate our lives: as we clasped hands and shed tears while the neurologist pronounced those unfamiliar words – motor neurone disease – and told us that ‘typical progress’ was 2-3 years; as the clinic nurse empathetically asked about 6-year-old Kimi and cursed the shit sandwich; as we started to tell family; as we reeled and howled and talked and hugged through that first day of all the stages of grief.

I did not expect to make it the next day, as in its early sleepless hours I started reading, and found not only the wonderful MND association publications for children – which equipped us to gently answer Kimi’s questions that started that morning with enough truth, with the important certainties of love and science – but also numbers. I found life expectancy statistics, the distinction between medians and mean somewhat blurred. I preferred the Australian reported figure of 27 months to the UK 14 months, and hoped with this as the median I might be in the lucky 50% who made it to 27 months (understanding I had the same chance of dying sooner) and didn’t dream I would still be alive in 4 times that.

I didn’t expect to make it as I started to share the news with dear family and friends, exchanging our love and shock and grief and hope and fear. We were embraced with such generosity of loving support: offers of meals and company and fundraising and gifts and lifts and sewing and organising and prayer and immediate and ongoing care for Densil and Kimi; practical advice from those with lived experience or research knowledge in disability and healthcare and superannuation and advocacy and coming out and chronic illness and parenting and bereavement and dying; and MND stories. I found that this thing that hadn’t been on my radar was on the radar of so many friends, with direct experience of MND amongst their loved ones and colleagues and communities. Their stories emphasised reasons for hope, those who had lived longer and remained true to themselves, the large, light-filled, lingering presence of bedridden yet entertaining grannies and still-working, world-changing colleagues. I had to dig for, or leave unspoken, the heartsore tales of rapid progression that often lurked beneath understanding quiet mentions of ‘personal experience’ and ‘other friends’ and ‘family connection’.

I didn’t expect to make it as I met with and quizzed and relied upon my expansive healthcare assemblage. My kind and thorough GP, Anna, who guided my diagnostic journey and unnecessarily apologised for weeping with me when we met two days after my diagnosis, has been steadfast and adaptive in her care, adopting home visits and written communication. My fabulous MND neurologist, Dom, initially emphasised the variability and uncertainty of individual trajectories and a sense of urgency, start your stand-up comedy career do it now before it’s too late: his deep knowledge and warm, personal commitment to his patients and their families has since proved to be literally lifesaving. Early meetings with the first of my occupational therapists, physios, speechies, dietitians and so many other good people who have supported me along the way often included gentle questioning to check that I understood the need for urgency that accompanies this ferocious disease.

I didn’t expect to make it as I became part of the MND community. In my first few days I joined MNDNSW, encountering reassuring advice when I spoke to David on the infoline, and being visited by energetic regional advisor Jo, who urged a flurry of organisation to get supports in place before they were needed and cited advances in genetic research to promote a hopeful ‘never give up’ attitude (but knowing the long, arduous, precarious journey from laboratory discoveries to approved, effective treatments, at least in pre-Covid-19 ‘old normal’ times, I mentally translated this to be hope for future others rather than for me). I started to meet gorgeous people with MND and their heroic families at association events, through mutual friends, and participating in fundraising and awareness campaigns; social media helped to augment these friendships but also to connect with MND families not only in surrounding suburbs and wider Sydney but across Australia and around the world. Apart from its membership requirement, it’s a privilege to be part of this ‘club’: a diverse community of compassionate, creative, funny, thoughtful, beautiful people. The awful flipside of getting to know and love people with MND is the inevitable heartache of losing them, grieving these precious people and for those left behind. As I saw this reality of how quickly MND can take people, regardless of their inner strength or how much they are cherished, I felt no reason that I would be spared.

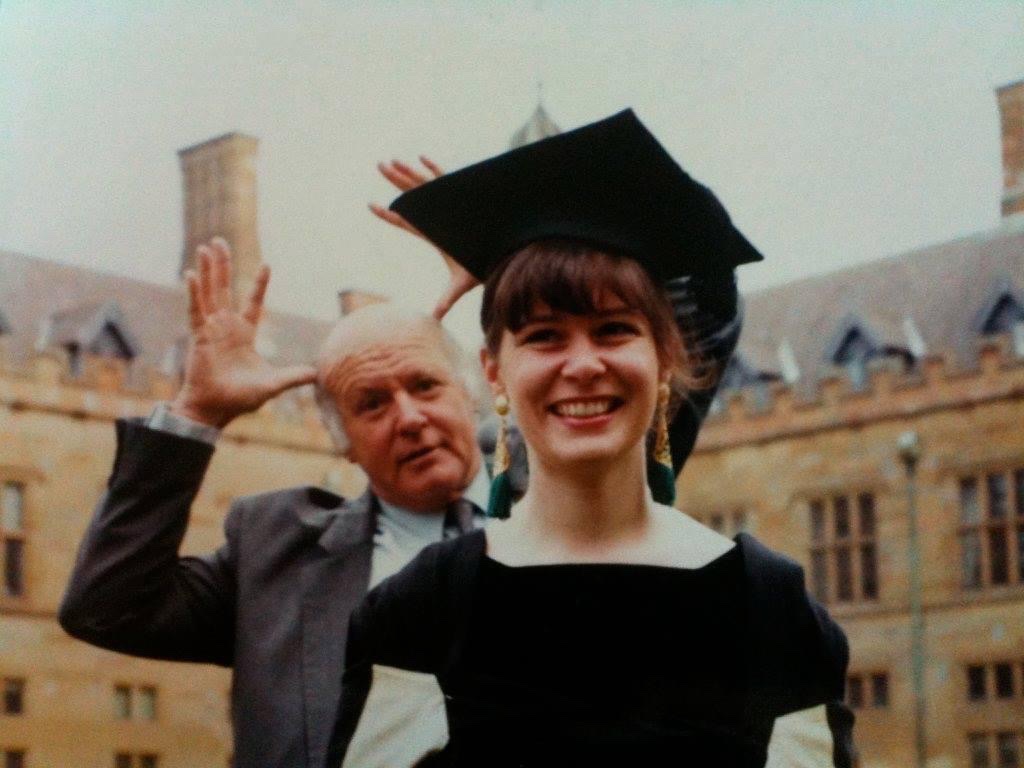

I didn’t expect to make it as I witnessed my bodily transmogrification. In the nine years prior to diagnosis my strong body had travelled the world, run a half marathon in my first trimester of pregnancy, birthed our daughter, done a 10km ocean swim, completed a PhD and worked as an academic, and so much more. Subtle changes – cramping in my legs and fatigue when I exercised, tripping over my feet, loss of fitness, spasms in my hands – in recent months had propelled me towards my diagnosis. Now the changes rapidly escalated, with increasing fatigue and weakness and reliance on a succession of more and more items of equipment and help to manage less of what I had previously taken for granted. Within 27 months of diagnosis I had completely lost the ability to take a step forward while leaning on a walker, and spent most of my day in my power wheelchair. Densil and I had moved out of the bed we had shared for 23 years so that I could sleep in an adjustable hospital bed: raised to its maximum height, Densil or a carer could pull me into a standing position and plop me onto my shower/toilet commode – soon I would need two carers and a hoist to transfer. I was still reliant on my morning carers or family or friends to get me on and off the loo (cue 1986 song of the year): a suprapubic catheter the next month came just in time and at least addressed number one challenges (I will spare you the details of number two, except to say that I am not the repository of all wisdom) but also marked the end of the pleasure of hydrotherapy. My arms were well past the point of being able to hug my family, shower or dress myself, type on a laptop, lift a coffee to my mouth or sign my name, and my neck muscles could only support my head for short periods; but I could still, then, push my wheelchair joystick, drink from a strategically placed straw, type on a mini iPad, and with elbows braced against my armrests perform a two-armed manoeuvre to press the traffic light button. I could see the direction my body was heading in: I knew I was lucky to have made it through 27 months, and didn’t expect to reach four and a half years, let alone nine.

I certainly didn’t expect to make it as breathing became a struggle. In one of my early appointments with Dom I asked how rapidly my MND was progressing. “Too [alliterative participle] fast” was his short answer, softened with the advice that respiration, nutrition and hydration were the functions critical for life and these could be supported when the time came. Before each MND clinic appointment I spent the night with a fancy pulse oximeter gripping my finger to record my blood oxygen sats while I slept. The respiratory physician explained that respiratory muscle weakness usually manifests initially overnight as dips in oxygen and consequent disruption of sleep, and that in a “typical course” of three years, respiratory failure occurred for the last year. I was oxymoronicly both hyper vigilant to, and in wilful denial of, the accumulating signs that my breathing wasn’t what it used to be: needing my head elevated to sleep, puffing with the exertion of moving, delegating birthday candle blowing, waking tired, waning appetite and consuming my fat stockpile despite my crème brûlée regimen, quietening voice. And deepening dips in my nocturnal oximetry. A couple of months off my fourth diagnosversary, with the need undeniable, I started spending my nights tethered to a bipap machine, which supported my weakened diaphragm by pushing air in and out of my nostrils – a change which improved my physical comfort and undoubtedly prolonged my life but emotionally signified my approach to The End. Within 9 months, after three emergency admissions to hospital in serious respiratory distress, I was reliant on Masky McMaskFace around the clock. In March 2018, we eagerly watched an episode of Australian Story featuring Professor Justin Yerbury, who I had met talking about his MND research before and after his diagnosis with a hereditary variant that ran through his family, and who we learned was still alive thanks to having received a trachie two months earlier – something I had previously asked the respiratory physician about and been told it wasn’t done in Australia. In a subsequent meeting with my GP and neurologist we talked about this possibility – one that Dom emphasised that only a handful of his patients had pursued (I seem to recall a metaphor involving spheres and metal) but that opened the magical potential of making it to my next anniversary and more. We were able to talk and investigate and articulate our sense that life – even in this strange, utterly dependent, deteriorated and deteriorating body – was worth living. Thus, on the third of November, 2018, when plummeting oxygen and blood-poisoning buildup of carbon dioxide forced me into a sleep that was very likely to be my last, as my life dangled on a gossamer thread, my darlings Densil and 12-year-old Kimi when ushered into that sacred, scary hospital conference room, and Dom in a long phone call, told the Emergency doctors that I didn’t wish to quietly slip away, that they should try to resuscitate me. And (thank God, thank Science, thank diligent, expert medical care), after six hours of being on – maybe beyond – the brink of life, I woke up. In the next couple of weeks, of being transferred between hospital ICUs, talking with surgeons and specialists, having precious final conversations in what had become of my voice, our inclination to prolong my life crystallised into a decision to go ahead with a tracheotomy and laryngectomy. Within the week, surgery completed, a ventilator connected through a hole in my neck was breathing for me, I was speaking in the voice of Ryan, I was hydrated and analgesed via an IV drip, I was ingesting isosoy, drugs and coffee through a tube up my nose. I was alive. And making it to nine years was no longer an impossible dream.

As i have been writing this, on and off, over the past month and a bit, I have been feeling grateful for nine years, for my ninth year, for this baker’s dozen last month, for each of these 3321 (see what I did there?) days.

The past year has been a terrible one for so many, in a no-longer-unprecedented way. Despite Ryan’s pronunciation, the effects of Omicron have not been micro. For those of us in the MND and broader disability community, Covid has brought extra challenges and fears – vulnerability to the disease, the health of loved ones and carers, safe access to essential supplies, what happens if we, family or carers become sick or have to isolate, policy settings and rhetoric that dismiss the lives of people with disabilities, availability of healthcare and hospital beds, evaporation of opportunities to carpe diem, compounded mental health issues, and more – with the minor compensation of online delivery and community empathy. But the year also held treasures, amongst them: occasional visits from dear masked friends; Grace Tame, Brittany Higgins and other brave women speaking out; rainbowfication of our Hills Hoist; our excellent MND and videogames team and other research/writing projects; Bruce’s weekly mandalas and lovely nieces’ artworks; Wordle; Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun, Lohrey’s The Labyrinth and other wonderful audiobooks plus much good radio and telly; joining the Your Story Disability Legal Service Advisory Group; beautiful new dresses (thanks Eleanor); our cat, shorn by the vet as part of – mercifully successful – treatment for paralysis tick, choosing my foot coverings as a preferred cosy spot to nestle (which lost its gloss when, two weeks on, he performed his telltale dance and, tail aloft, peed on me); and witnessing little Elspeth’s delightful explosion of meaning-making during our weekly family FaceTimes and, finally, RAT-proofed face-to-face family gatherings.

The shiniest, richest, most glorious treasure of this year has been another year with my Densil and Kimi. I fell in love with Densil 35 years ago, when we were practically babies, and this year will be our thirtieth wedding anniversary. I still love, like, admire and enjoy him – his wisdom, cheeky smile, eclectic interests, gentleness, astute insights, perfect pitch, care, subversive wit, practical problem-solving, deep intelligence,

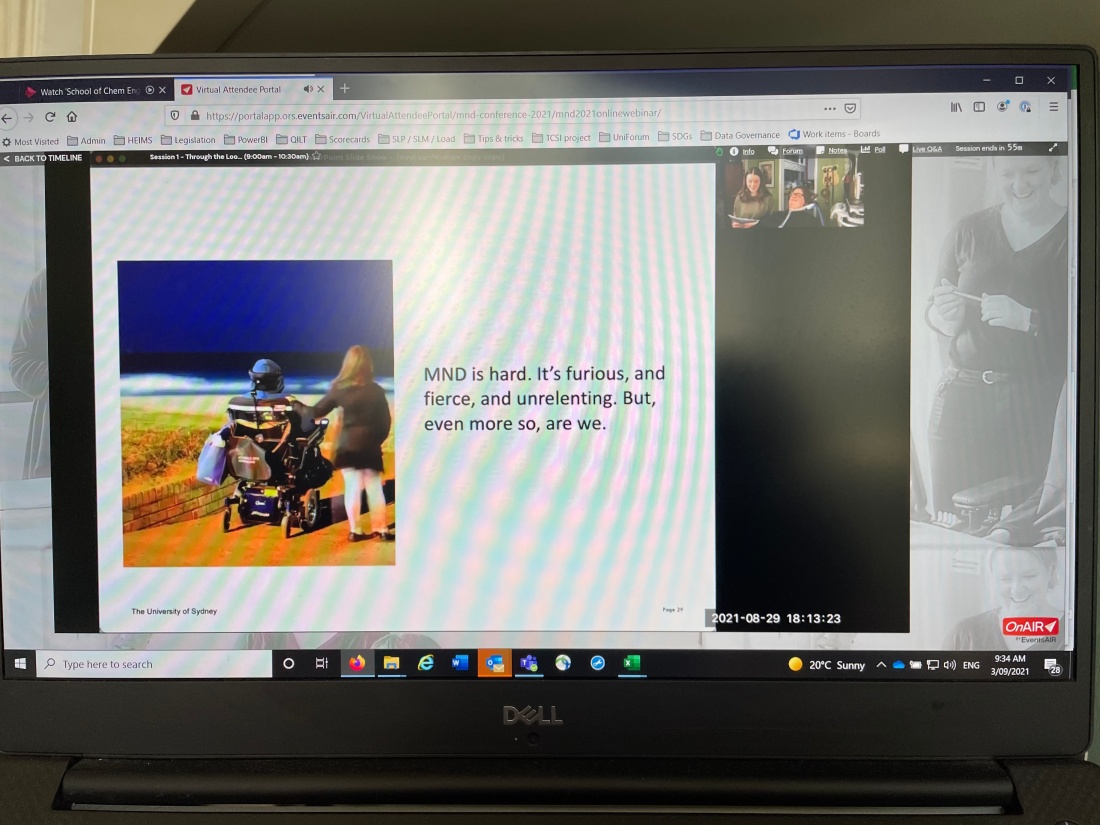

The shiniest, richest, most glorious treasure of this year has been another year with my Densil and Kimi. I fell in love with Densil 35 years ago, when we were practically babies, and this year will be our thirtieth wedding anniversary. I still love, like, admire and enjoy him – his wisdom, cheeky smile, eclectic interests, gentleness, astute insights, perfect pitch, care, subversive wit, practical problem-solving, deep intelligence, lustrous locks, world-knowledge, forbearance, quirkiness and creativity. I’m so thankful that I have been able to watch Kimi grow from a beautiful, kind, friendly inquisitive six-year old to a beautiful, kind, friendly inquisitive fifteen-year old. She has transformed from a well-behaved junior primary schooler two years in to a motivated, bright senior high schooler in her second last year; from a reluctant classroom speaker to my superb co-opener of last year’s national conference; from a Frozen and Deadliest 60 watcher to a sophisticated appreciator of Tarantino, Insiders, the Three Colours Trilogy and Mad As Hell; from a recorder squeaker to a grade 8 alto and bari sax funkster; from littlest cousin to enthusiastic big (and not so little) cousin; from a fan of Diary of a Wimpy Kid to a reader of Barthes and Silvey and Honeyman. She is wonderful, they are wonderful.

I know how very lucky I am to have had these nine years.

Nine years of family. Nine years of friendship.

Nine years of learning. Nine years of teaching.

Nine years of social change. Nine years of community.

Nine years of loving. Nine years of trusting.

Nine years of laughing. Nine years of crying.

Nine years of awareness raising. Nine years of celebrating.

Nine years of observing. Nine years of contemplating.

Nine years of writing. Nine years of playing.

Nine years of caffeinating. Nine years of adventuring.

Nine years of hoping. Nine years of remembering.

And amongst all the shit and joy, best of all, nine years of partnering, nine years of parenting.

The shiniest, richest, most glorious treasure of this year has been another year with my Densil and Kimi. I fell in love with Densil 35 years ago, when we were practically babies, and this year will be our thirtieth wedding anniversary. I still love, like, admire and enjoy him – his wisdom, cheeky smile, eclectic interests, gentleness, astute insights, perfect pitch, care, subversive wit, practical problem-solving, deep intelligence,

The shiniest, richest, most glorious treasure of this year has been another year with my Densil and Kimi. I fell in love with Densil 35 years ago, when we were practically babies, and this year will be our thirtieth wedding anniversary. I still love, like, admire and enjoy him – his wisdom, cheeky smile, eclectic interests, gentleness, astute insights, perfect pitch, care, subversive wit, practical problem-solving, deep intelligence,

Sunday: as my two carers uncovered and cuff-pressure-checked and shoulder-massaged me from sleep I became conscious of the date, the eleventh Valentine’s Day anniversary of Dad’s death from mesothelioma. My grief has mellowed such that I am grateful to have so many happy memories and be aware of his lasting imprint on my life. As I was fed breakfast on the commode (you know it makes sense) I joined the end of an in(ter)continental zoom call with schoolfriends and heard about Nat’s life in lockdown Toronto and Sonya’s and Halfy’s reliance on communications technology. We acknowledged Dad during our weekly family FaceTime – my remarkable tech-savvy, community-building mum and Lexi with her digital-native, increasingly verbal (actually nominal) 420-day-old littlie in (hopefully snappy) lockdown Victoria; Sonia with cat and us in Sydney. I wondered how my soft-hearted, gregarious, self-confessed Luddite Dad would have coped with this age of Coronavirus. And I wonder what effect it will have on my niece and her generation.

Sunday: as my two carers uncovered and cuff-pressure-checked and shoulder-massaged me from sleep I became conscious of the date, the eleventh Valentine’s Day anniversary of Dad’s death from mesothelioma. My grief has mellowed such that I am grateful to have so many happy memories and be aware of his lasting imprint on my life. As I was fed breakfast on the commode (you know it makes sense) I joined the end of an in(ter)continental zoom call with schoolfriends and heard about Nat’s life in lockdown Toronto and Sonya’s and Halfy’s reliance on communications technology. We acknowledged Dad during our weekly family FaceTime – my remarkable tech-savvy, community-building mum and Lexi with her digital-native, increasingly verbal (actually nominal) 420-day-old littlie in (hopefully snappy) lockdown Victoria; Sonia with cat and us in Sydney. I wondered how my soft-hearted, gregarious, self-confessed Luddite Dad would have coped with this age of Coronavirus. And I wonder what effect it will have on my niece and her generation.